Explore significant moments in HarperCollins history

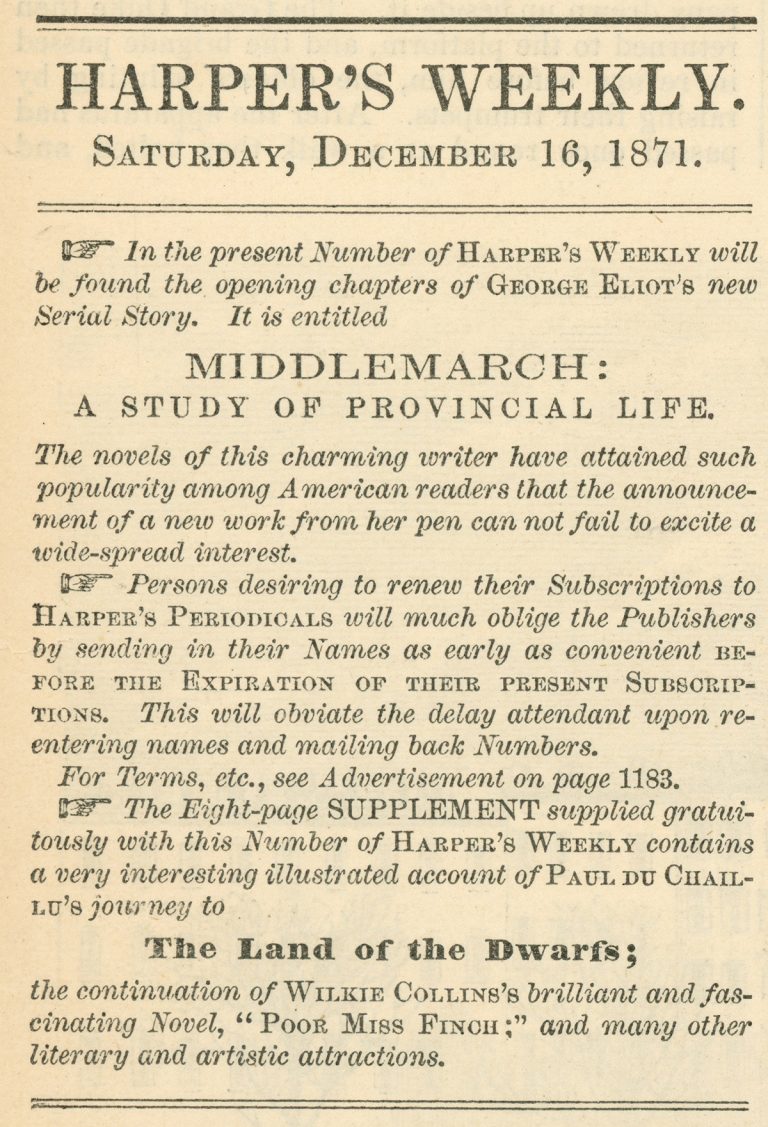

A snippet of the first installment of Middlemarch by George Eliot, which was serialized in Harper’s Weekly (December 16, 1871).

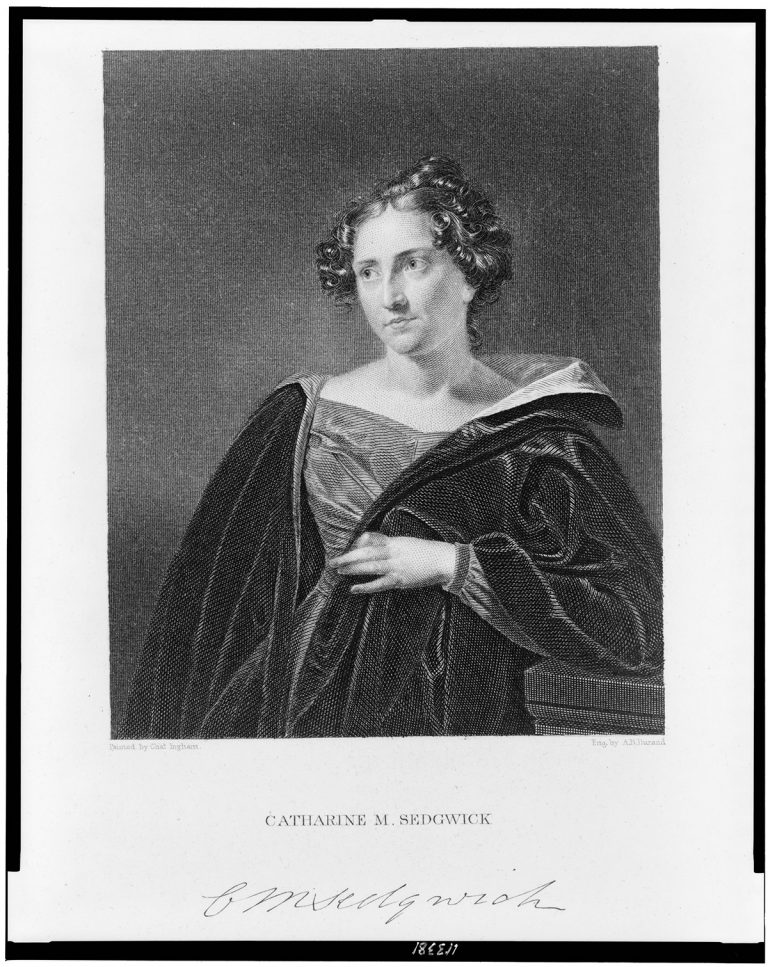

George Eliot

Mary Anne Evans, born in 1819, led a turbulent life that often broke with Victorian social norms. She rejected the church, lived with a married man, and later married a man 20 years her junior. Her family shunned her, and her decision to publish under the pen name of George Eliot derived from the concern that her private life would negatively influence the reception of her works. Her identity initially remained a mystery even to her English publisher, John Blackwood. Despite all this, George Eliot became one of the most acclaimed novelists of the nineteenth century, deftly exploring themes of social change and interaction in provincial English life.

Eliot’s success in America with Harper & Brothers as her publisher mirrored her success in England. Eliot’s novels Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1863), and Felix Holt, the Radical (1866) all sold well, as did Middlemarch (1872), which caused some friction in the New York publishing world. Publisher Ticknor & Fields had planned to release it, but for reasons now unknown, it ended up with the Harper brothers, who paid the author £1,200. The novel was first serialized in Harper’s Weekly and later published in two volumes, with a first printing of 3,000 copies. The firm significantly underestimated the demand and scrambled to print further copies.

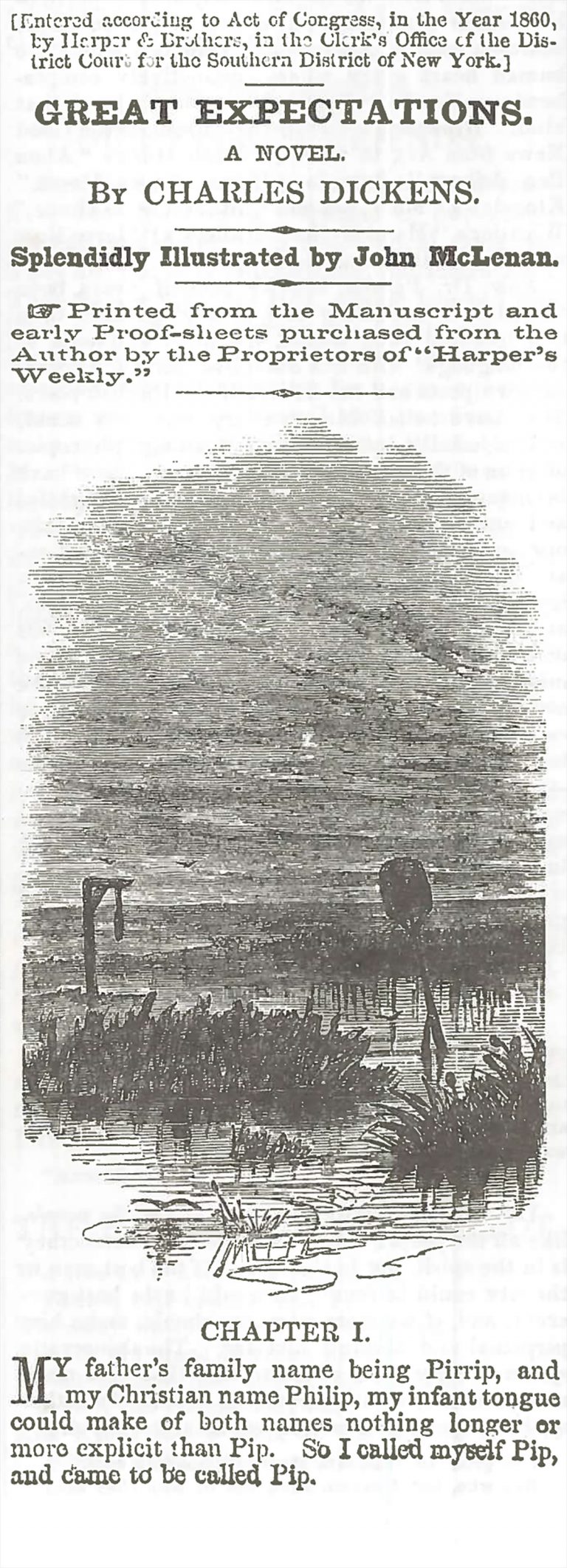

Despite concerns that Eliot’s final novel, Daniel Deronda (1876), would “appeal rather to the thoughtful few than to the great world of novel readers,” the Harper brothers paid her £1,700 for the work, a figure that Eliot’s husband described as “exceptionally large.” The amount surpassed by nearly £500 the sum that Harper & Brothers had paid a few years earlier for Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. Harper & Brothers printed 6,000 copies of Daniel Deronda and 15,000 more in “paper covers.”