Explore significant moments in HarperCollins history

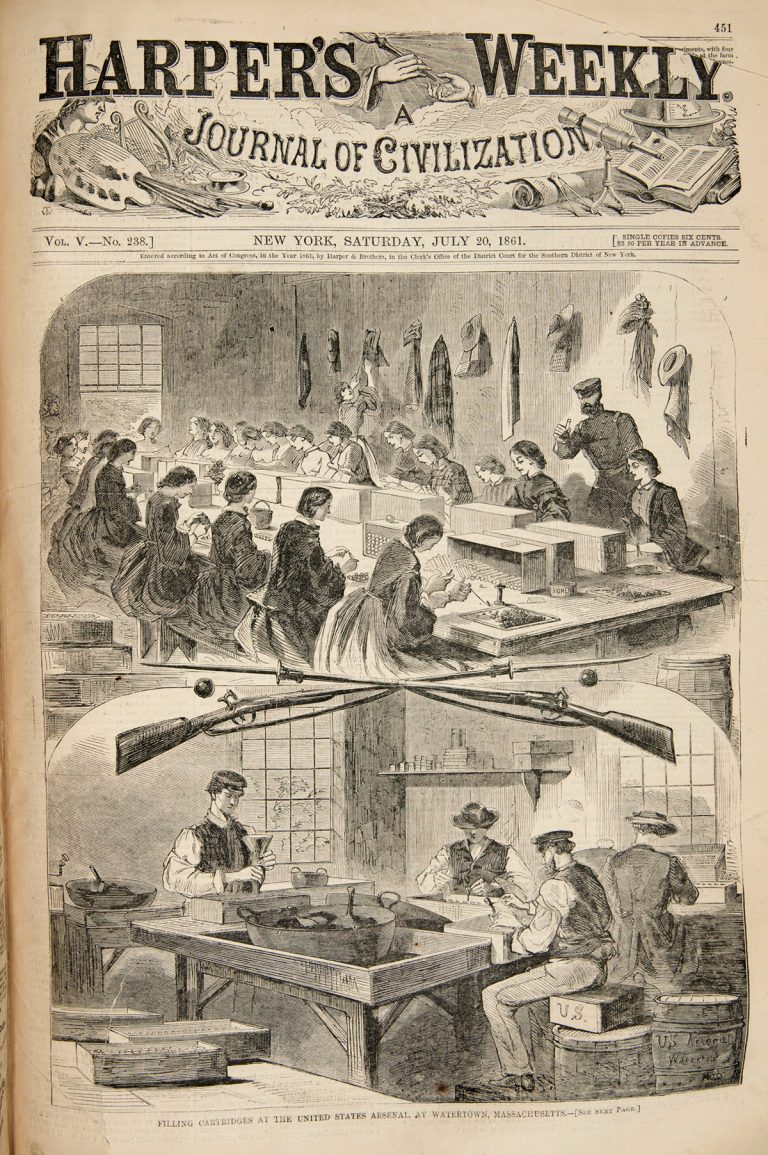

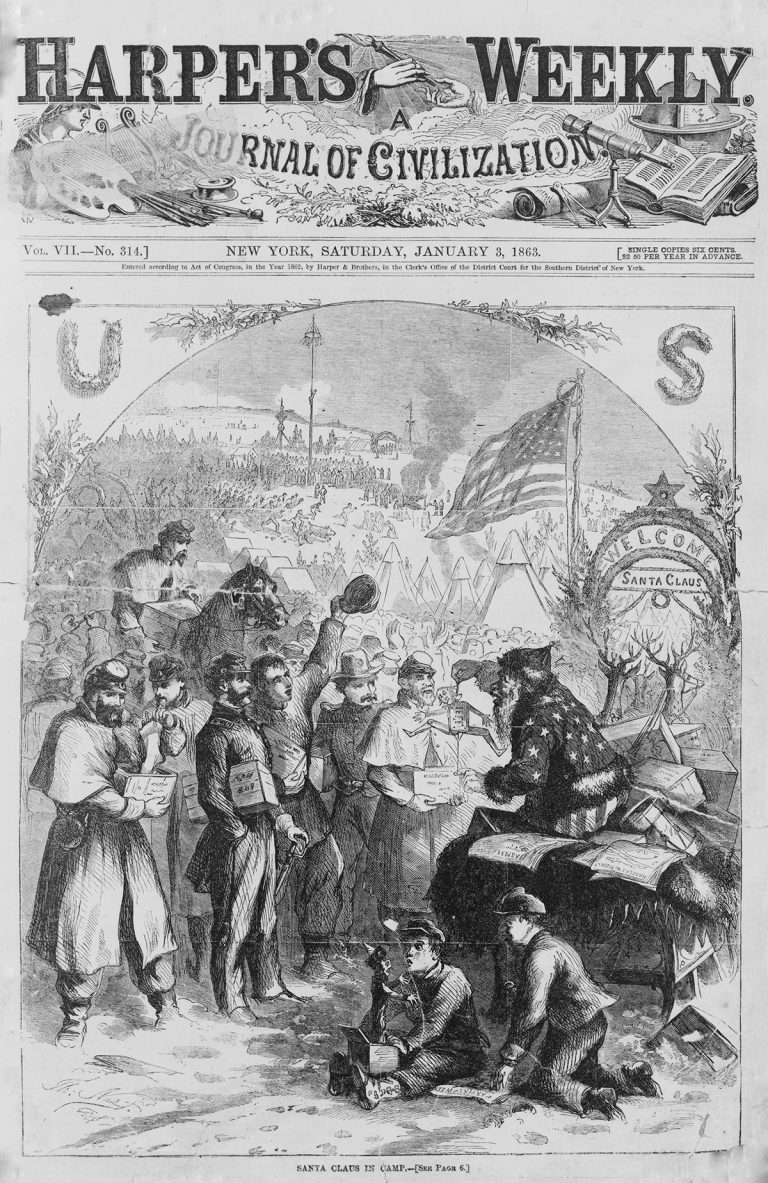

An illustrated cover of Harper’s Weekly just after the outbreak of the Civil War, dated July 20, 1861.

Social Change: The Harper Brothers and The American Civil War

Literacy became both a predictor of and influence on the American Civil War, being one of the disparities between North and South. In 1840, more than 80 percent of Northern children attended school, compared to less than 20 percent of Southern children. Despite near-universal literacy in the North, about 20 percent of white Southerners were illiterate. Only 5 to 10 percent of black slaves could read or write.

When South Carolina seceded from the Union and war became inevitable, the Harper brothers faced a tough decision: turn a blind eye to the polarizing war, or address it head on? Harper & Brothers chose the latter.

Fletcher Harper firmly aligned himself and the company’s periodicals like Harper’s Weekly on the side of the North, and he sent his best writers and illustrators to the battlefields. The Weekly’s reporting revolutionized war journalism, and circulation increased to 100,000, even with the loss of most Southern subscribers.

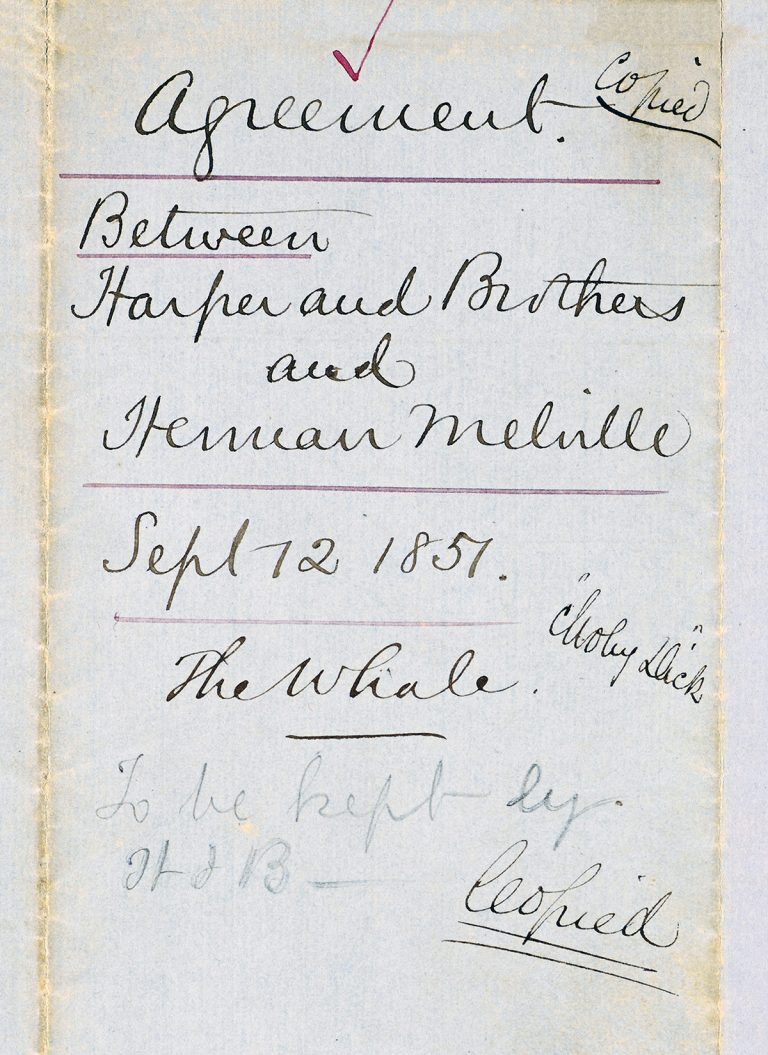

Harper & Brothers also published works on slavery, including Fanny Kemble’s Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation (1863). Journal was one of the few books to reveal the harrowing conditions female slaves faced on Southern plantations. Its popularity rallied public support for Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, providing evidence that a single book could influence not only public opinion but public policy as well. Later, Herman Melville’s Battle Pieces and Aspects of War (1866), a collection of 70 poems about the chaos of war, offered both Confederate and Union perspectives.

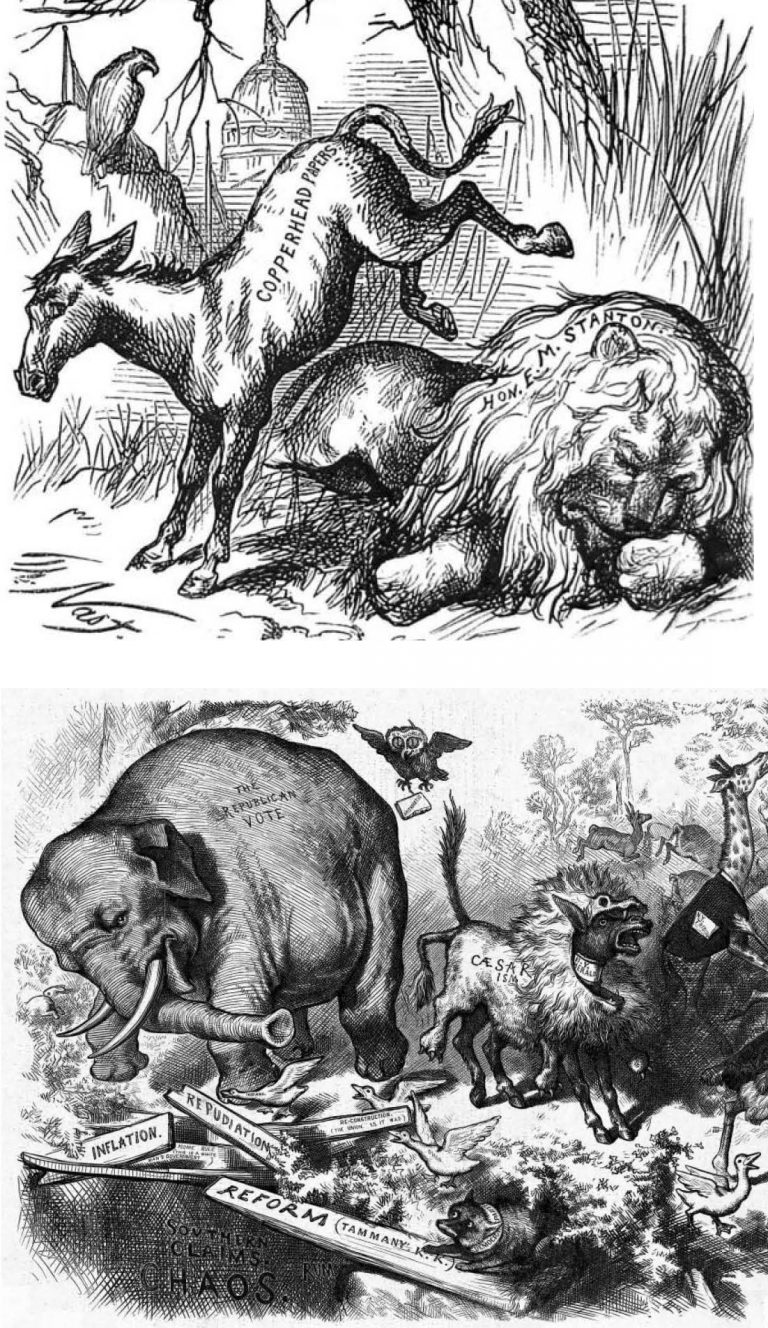

Colonel George Ward Nichols’s The Story of the Great March (1865) was another bestseller, and the brutally realistic Pictorial History of the Civil War (1868) by Alfred H. Guernsey and Henry M. Alden used nearly 1,000 illustrations that had been published in Harper’s Weekly. On the other side, G. F. Harrington’s Inside: A Chronicle of Secession (1866), illustrated by Thomas Nast, documented life in the Confederacy.